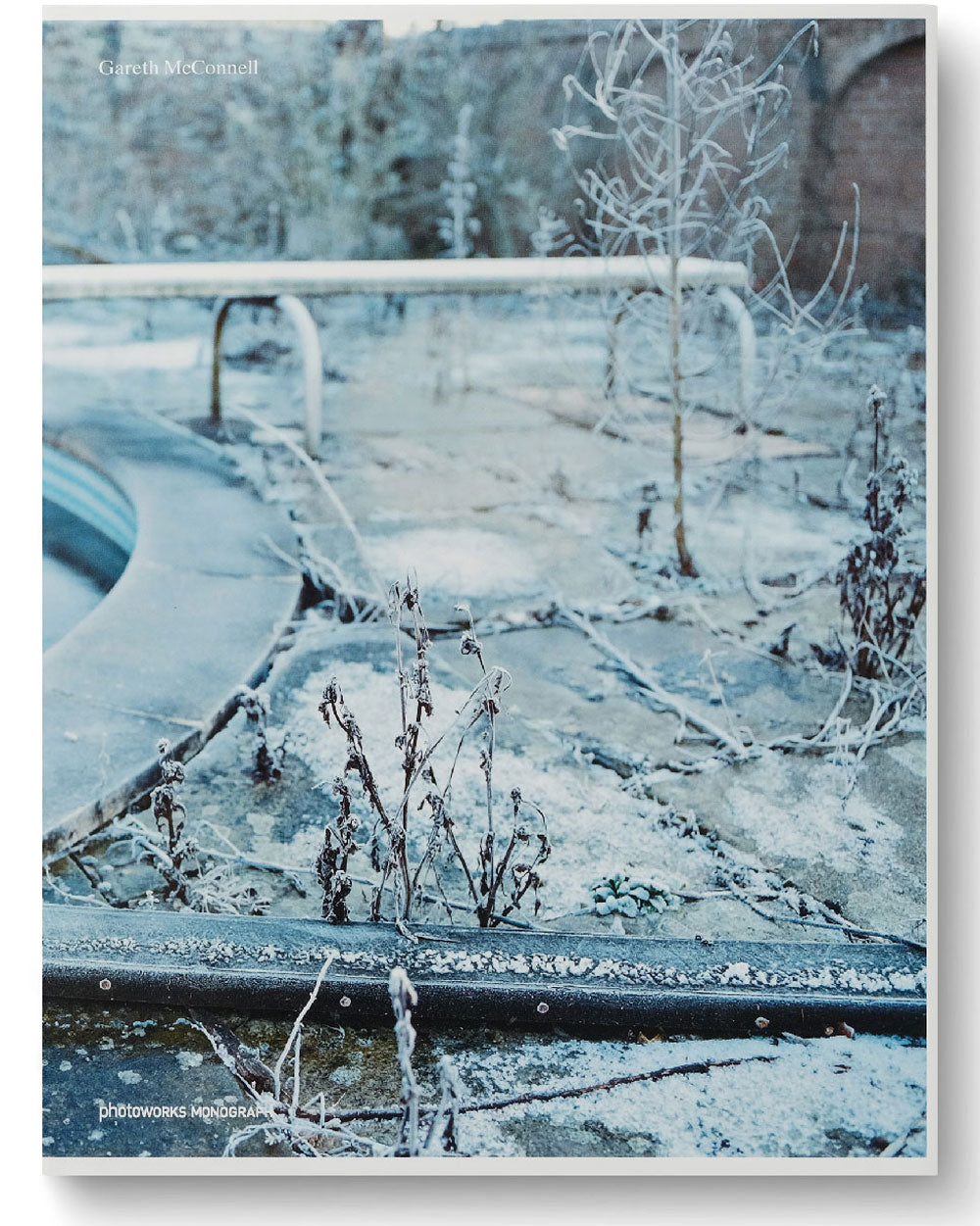

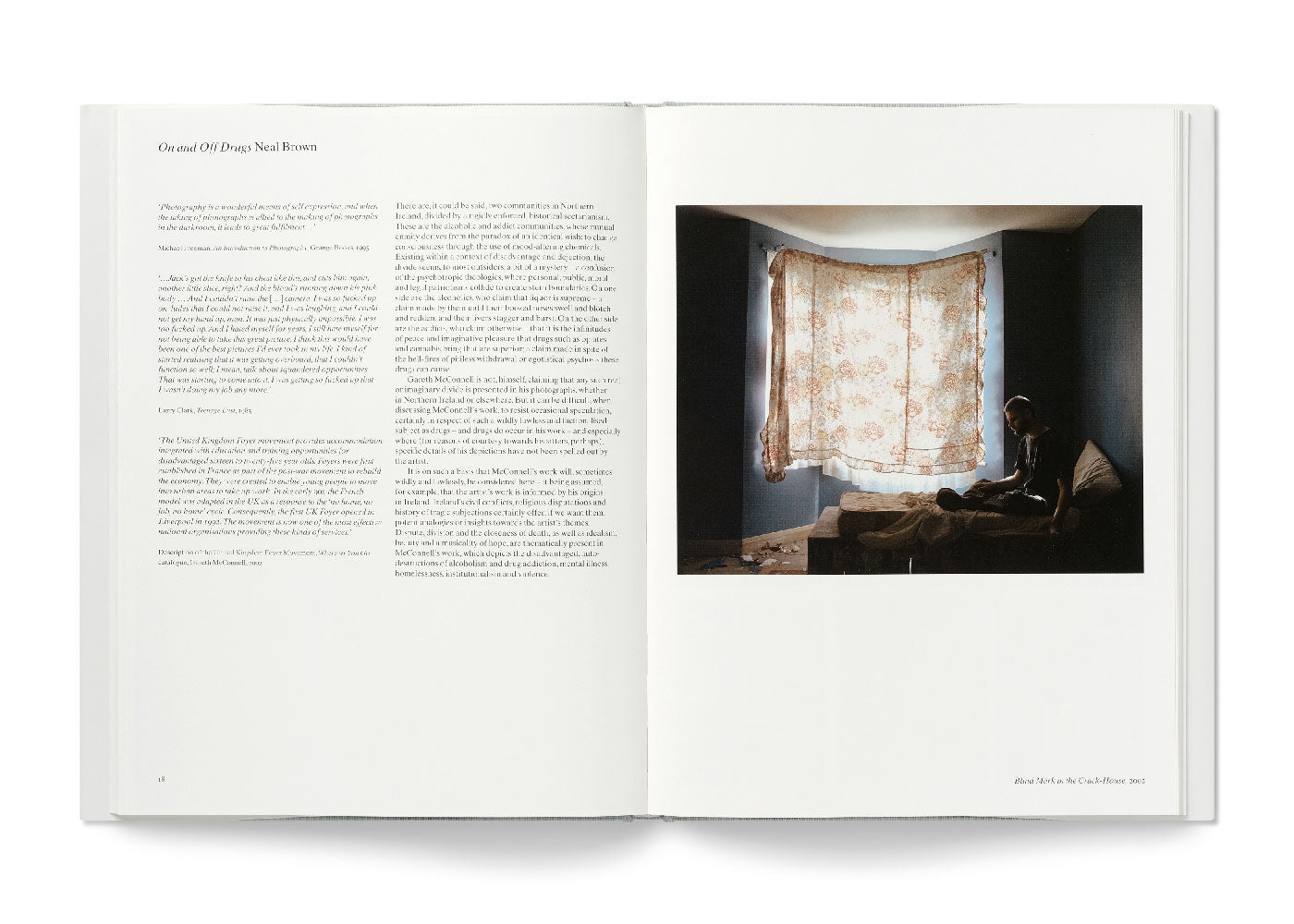

This book is part of a series of Photoworks monographs that surveys the work of the most important contemporary photographers in the UK. Comprehensively illustrated, and with specially commissioned texts, these substantial publications provide, for the first time, an overview of each artists work, acknowledging and celebrating their achievement to date.

_____

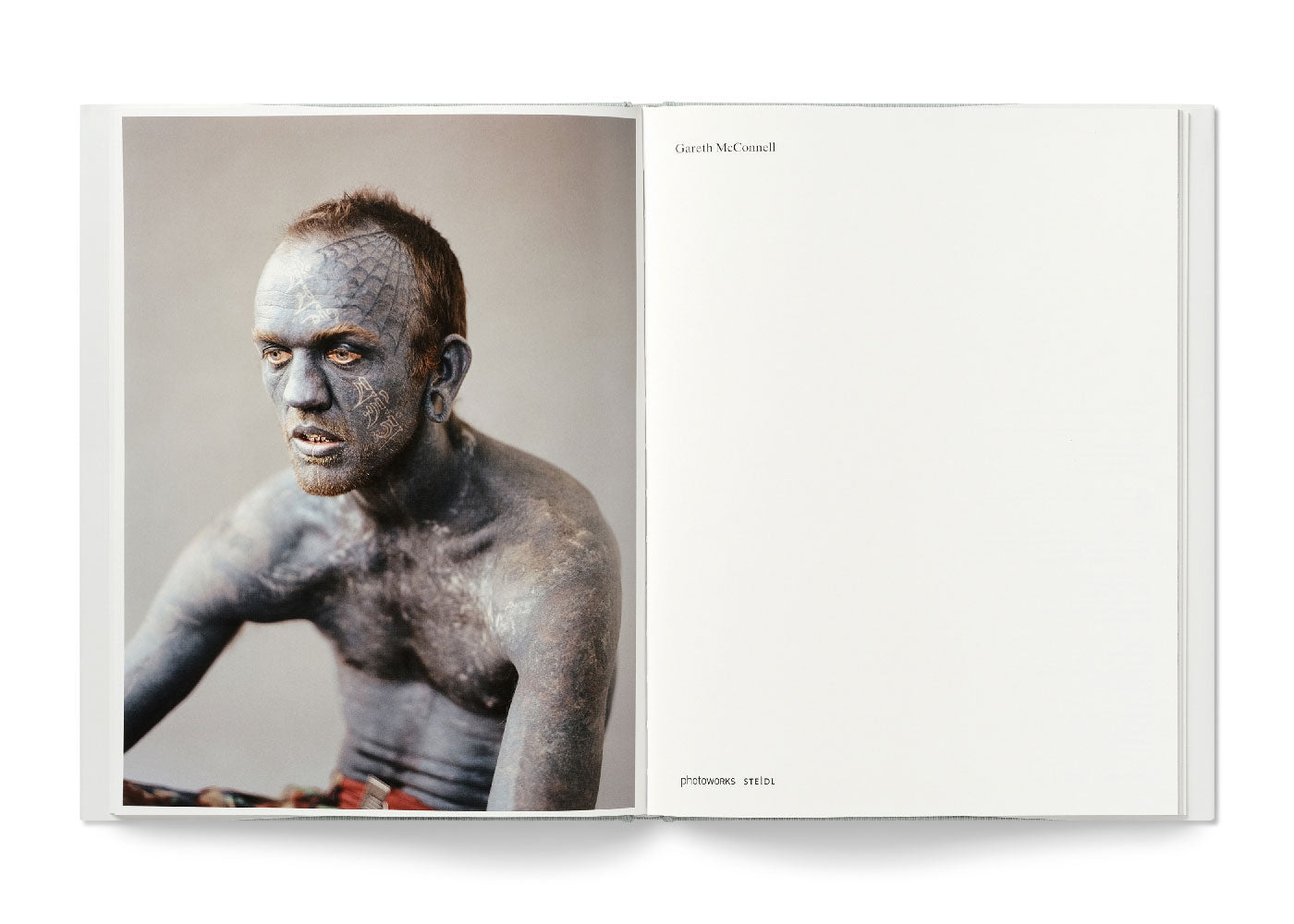

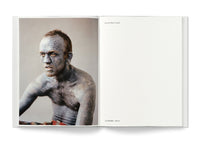

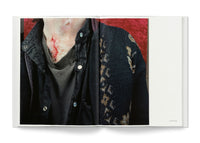

What’s so unnerving about the body is its lack of colour. The man is alive but not alive; his pink-rimmed eyes stare out as if already trapped inside something dying. In this extraordinary figure we might sense humanity itself held in some strange and uncertain balance, literally disappearing under an illustrated screen of tattooist’s ink, but also asserting itself in a defiant act of transformation and survival.

Welcome, this portrait says, to a place of extremes. And perhaps, to a place of endurance, too, where the ongoing struggle is that between mind and body, between severe acts of will and physical well-being.

That place and the photograph (Lucky Rich. The Most Tattooed Man in the World, 2002) which defines it are a fitting introduction to the work of Gareth McConnell, a young Northern Irish photographer who has, over the last five years, produced a succession of powerful and emotionally charged bodies of work that have established him, at a relatively early point in his career as one of the key figures in British contemporary photography.

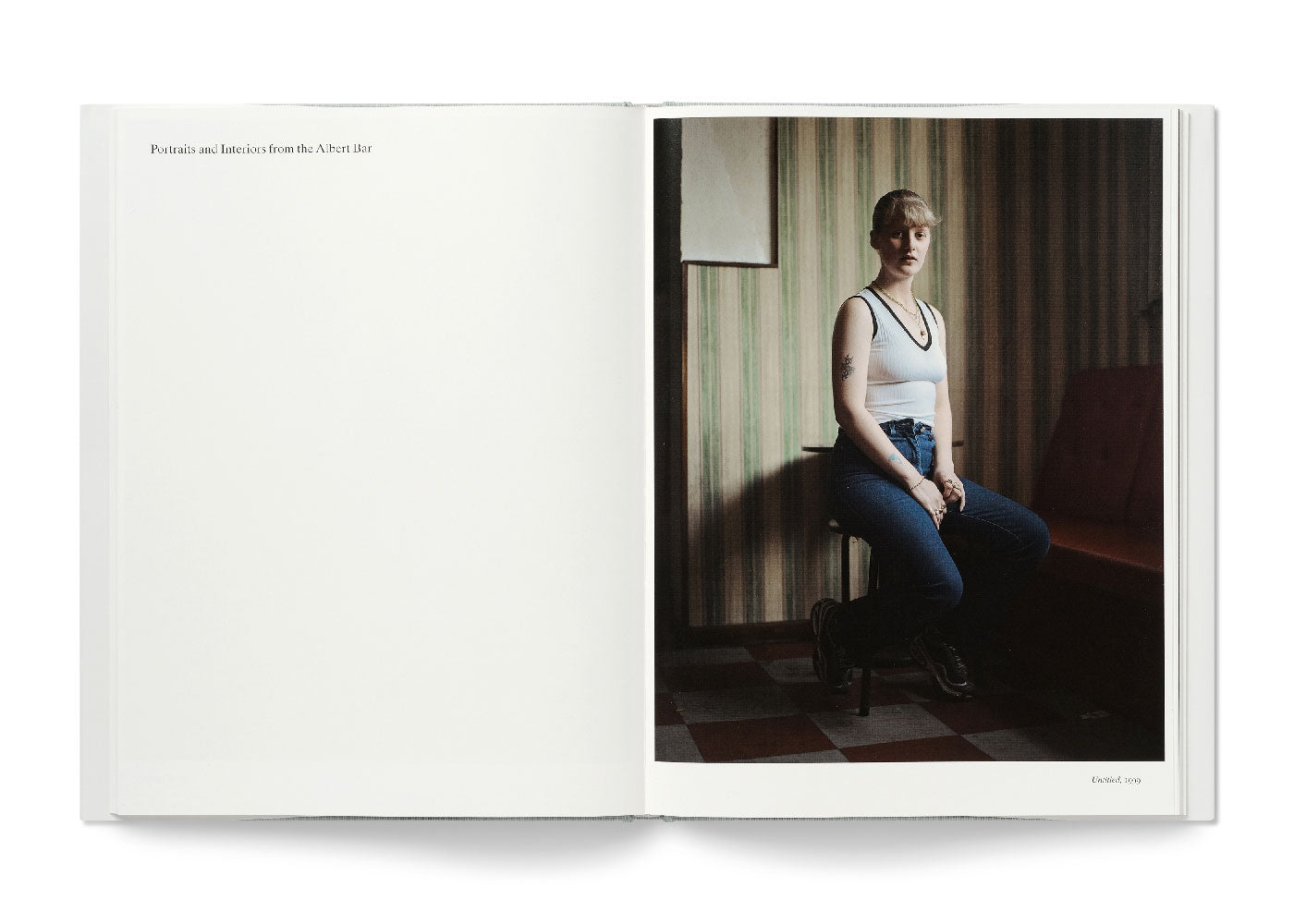

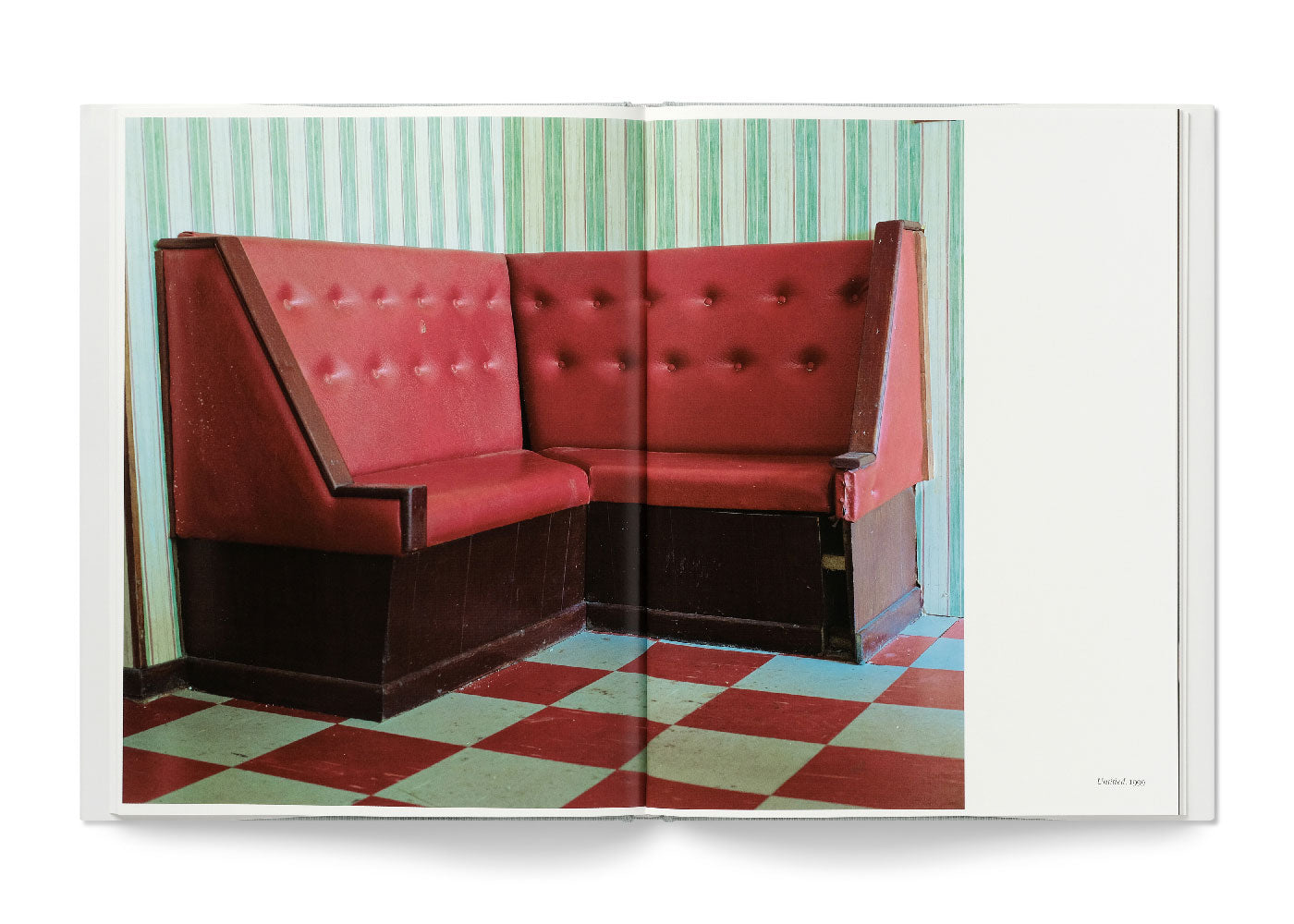

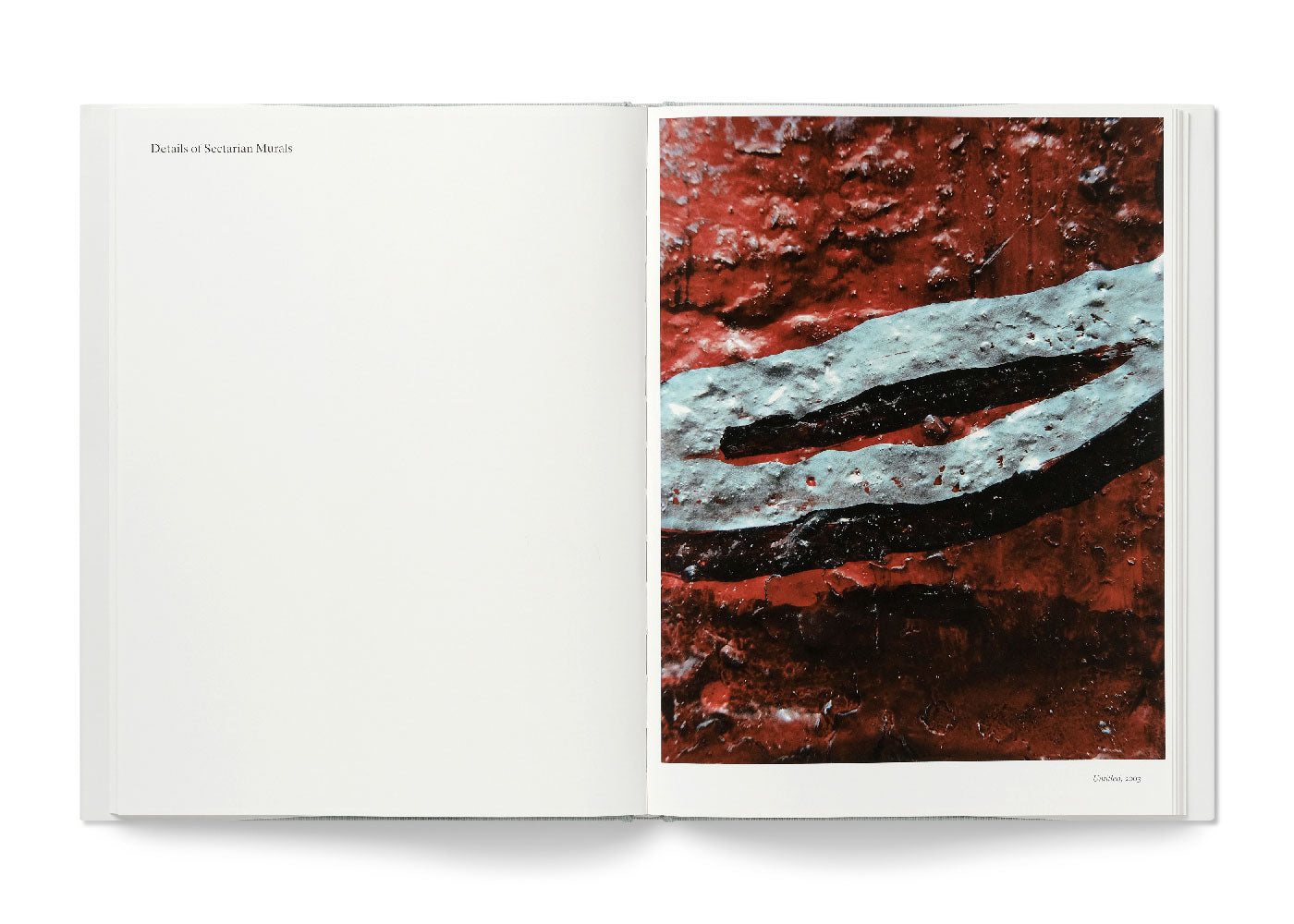

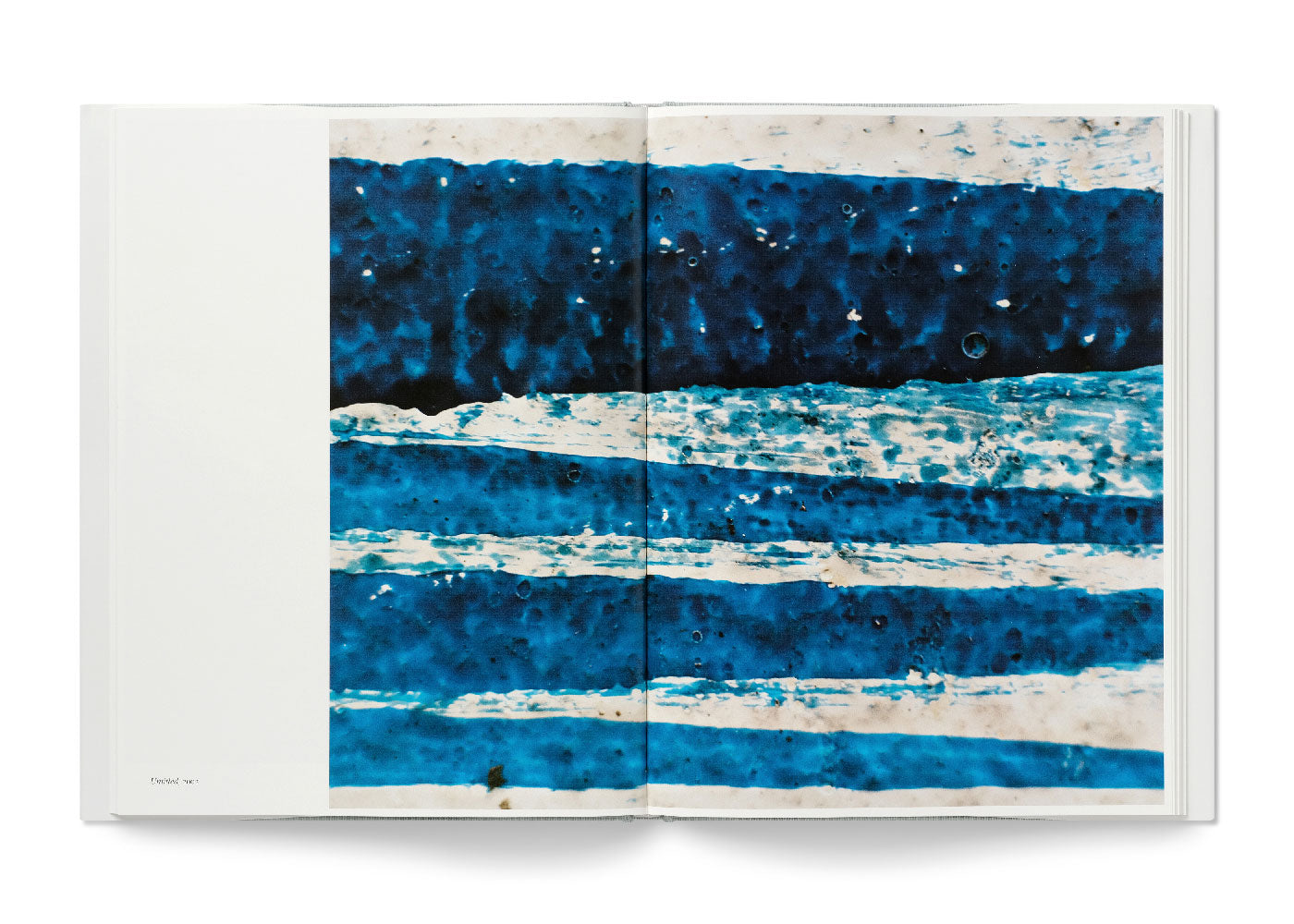

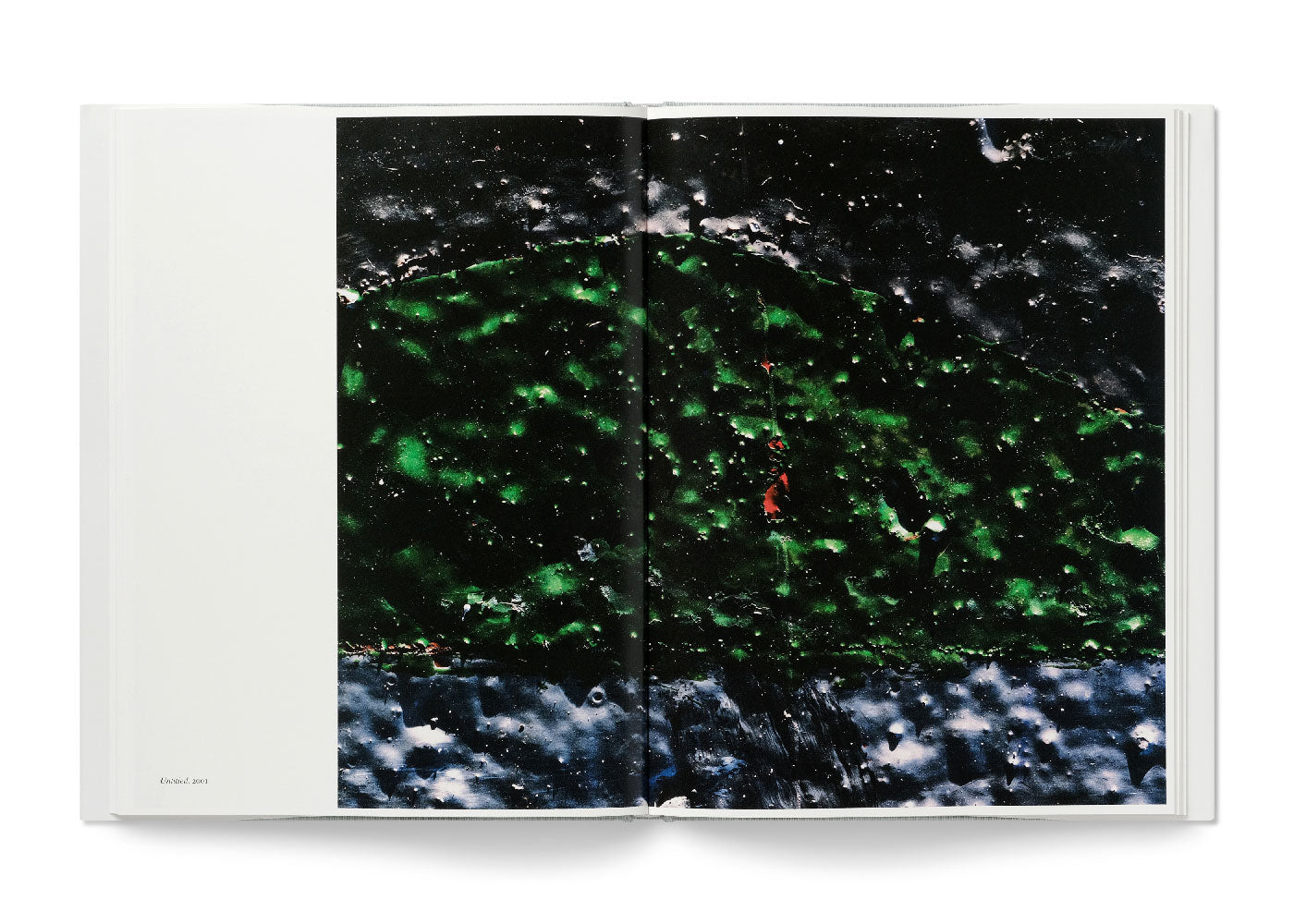

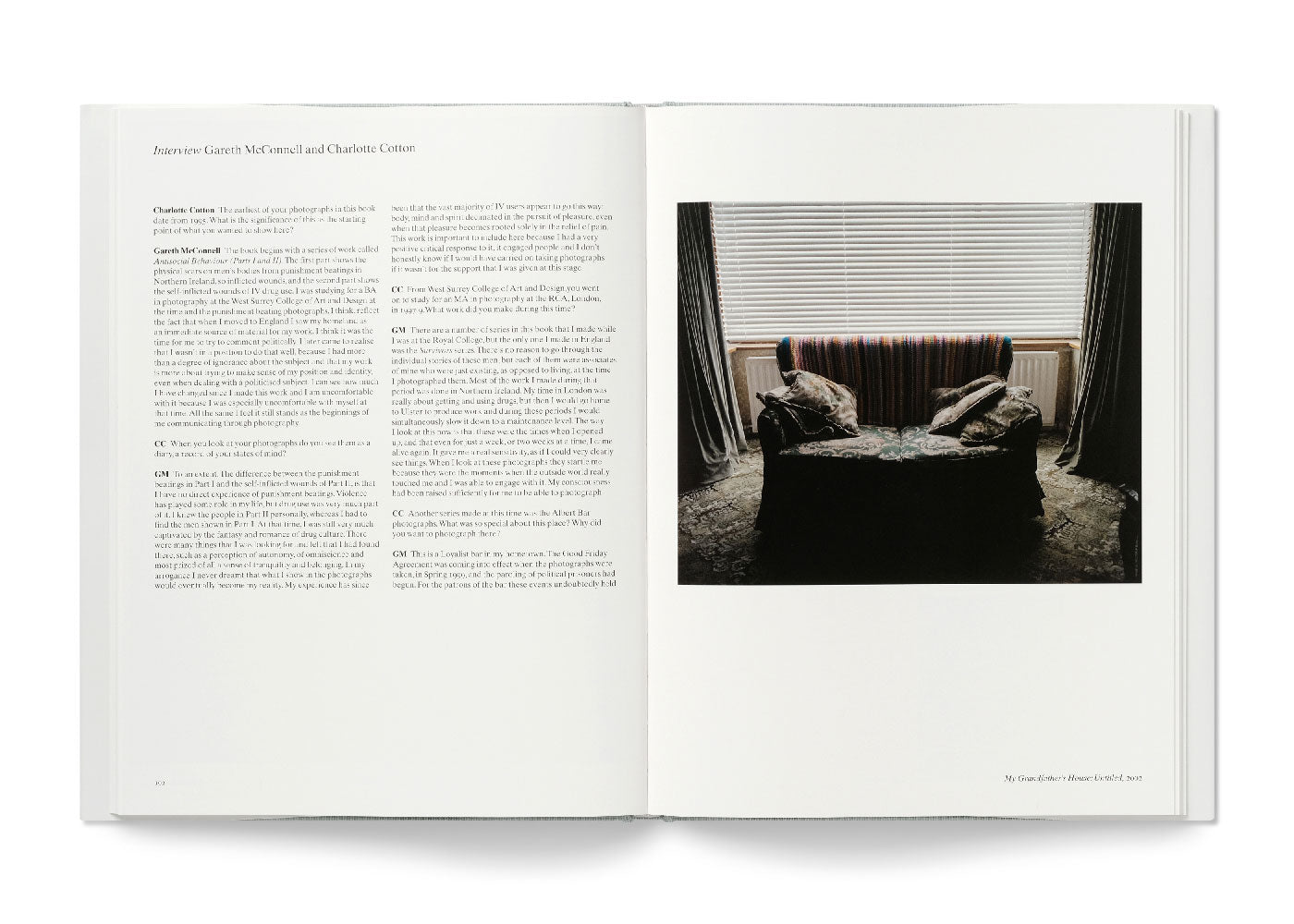

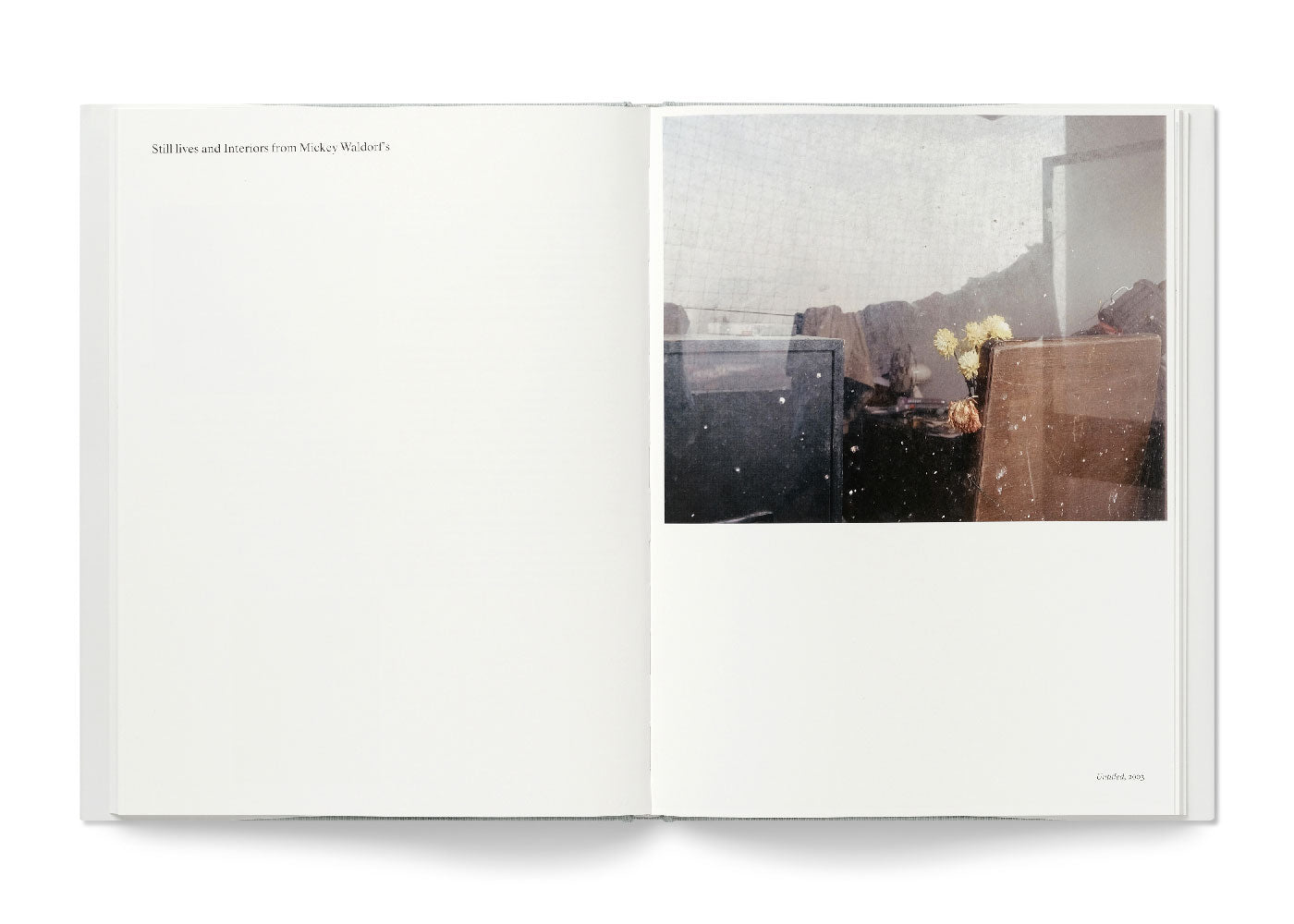

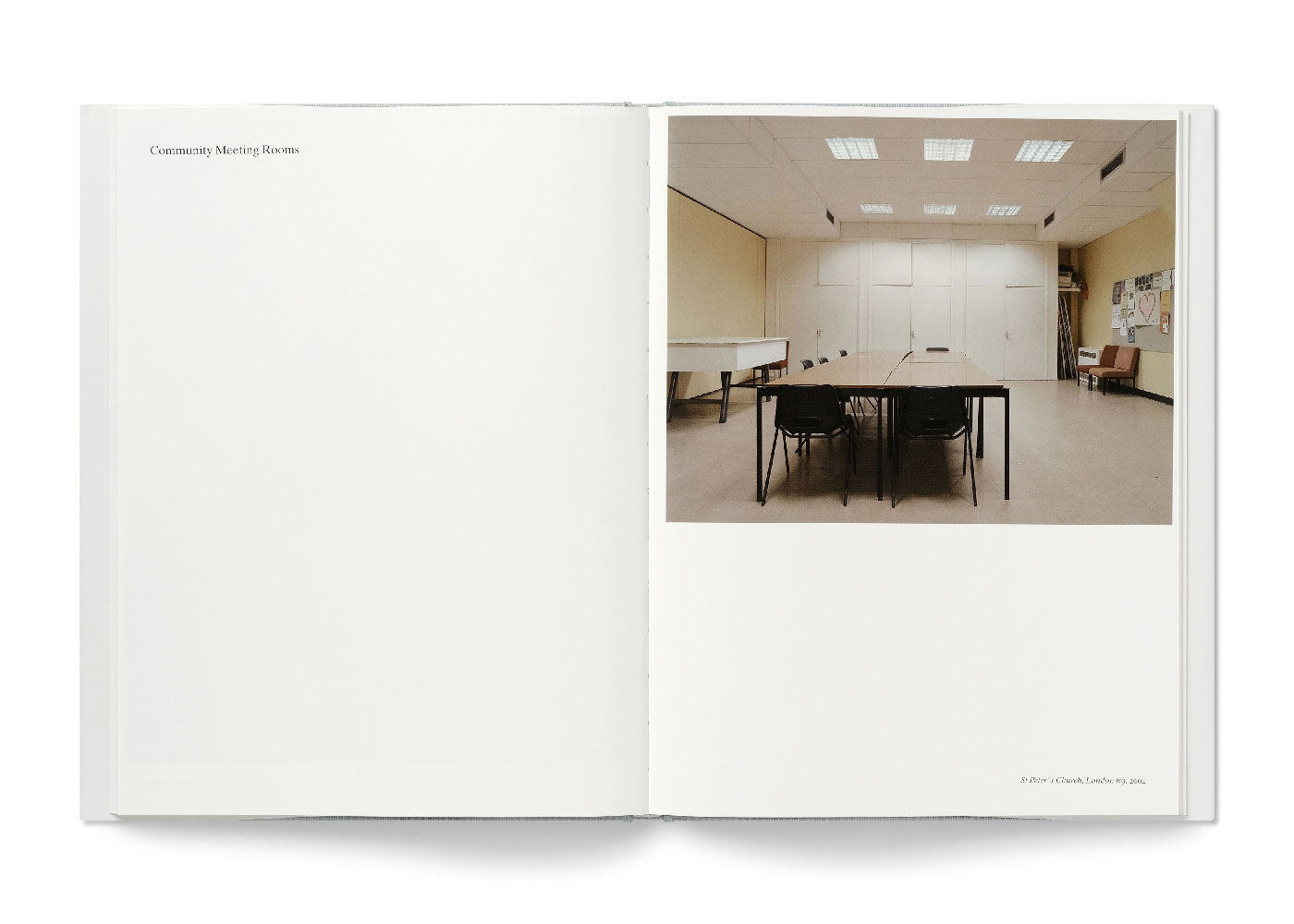

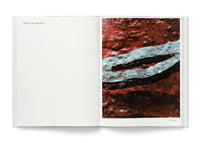

Born in Carrickfergus, McConnell’s life has been shaped by the violent tensions of Northern Ireland’s recent history. But the ‘troubles’ are not, or at least not overtly, his primary subject. Despite the presence of his disarming and already celebrated work from the Albert Bar in his home town and the oblique series of details from sectarian murals, the focus of this book is more personal, bringing together an intense series of works which encompass a period roughly 1995 to 2004, of similarly intense experience for McConnell. In fact it would be true to say that the photographs collected here mirror directly his own recent life in England and Ulster, and testify to a kind of maturity, but one of existence turned inward rather than opening out, expansive and worldly.

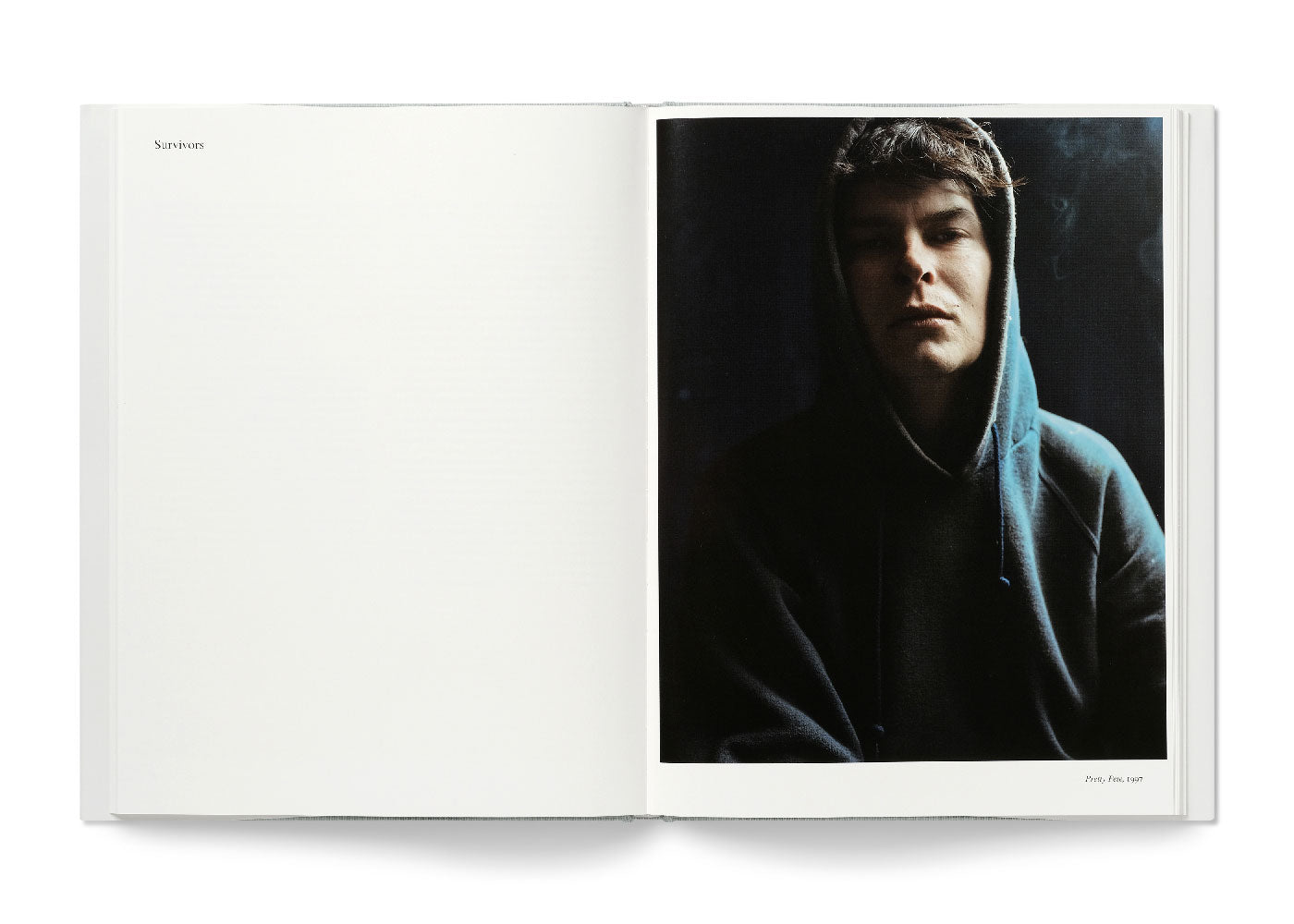

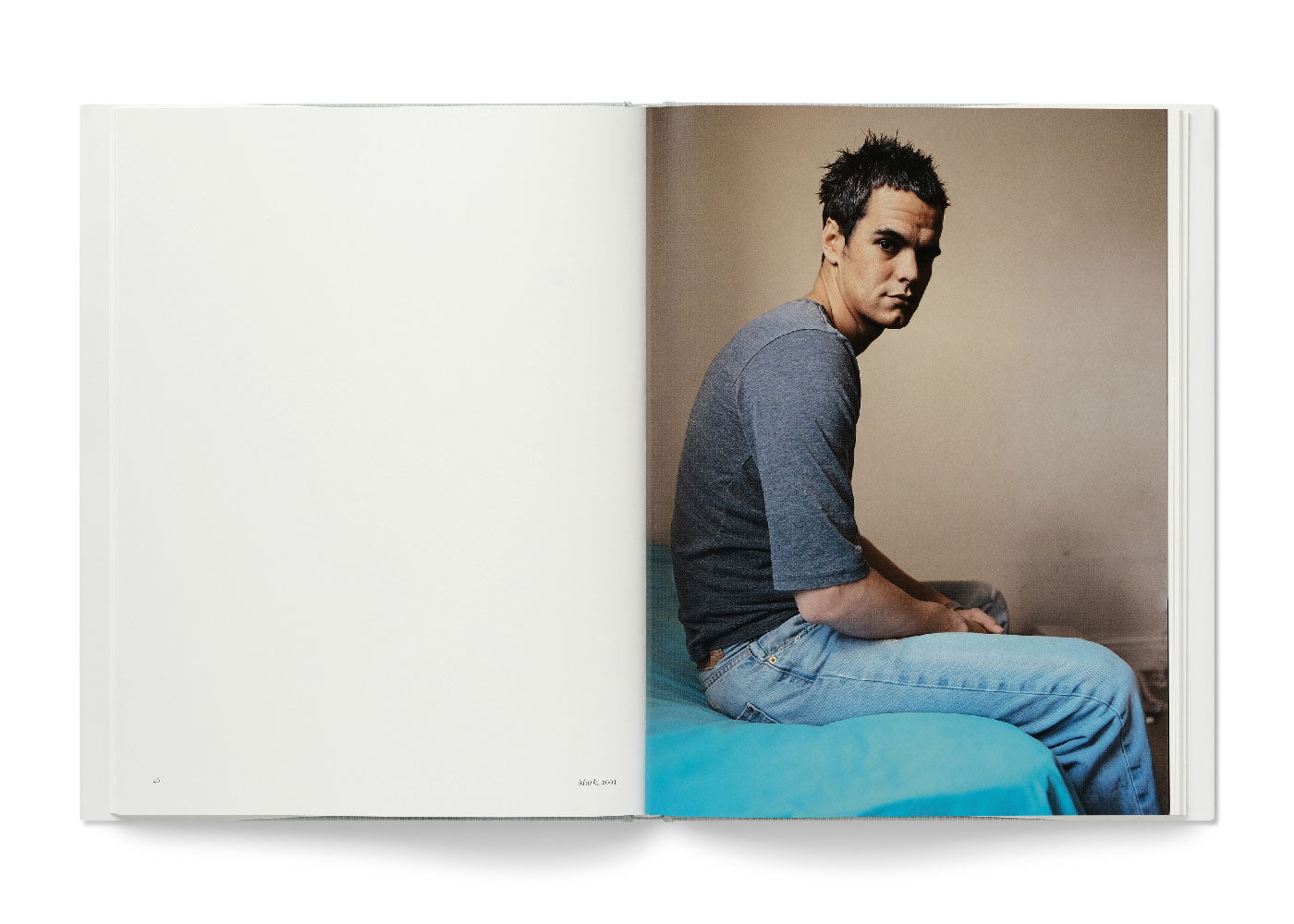

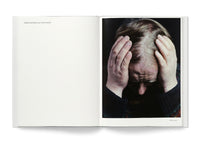

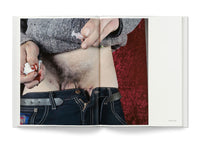

If one of the strongest impressions from McConnell’s work is that of youth drained and wearied by experience, by drugs, by excess and by the frailties that that experience leaves in its wake, then, importantly, his work is about strength and resilience, and the assured signature of the photographs themselves, their natural solidity and directness, is a sign of his own capacity for working through, for resolving and enduring.

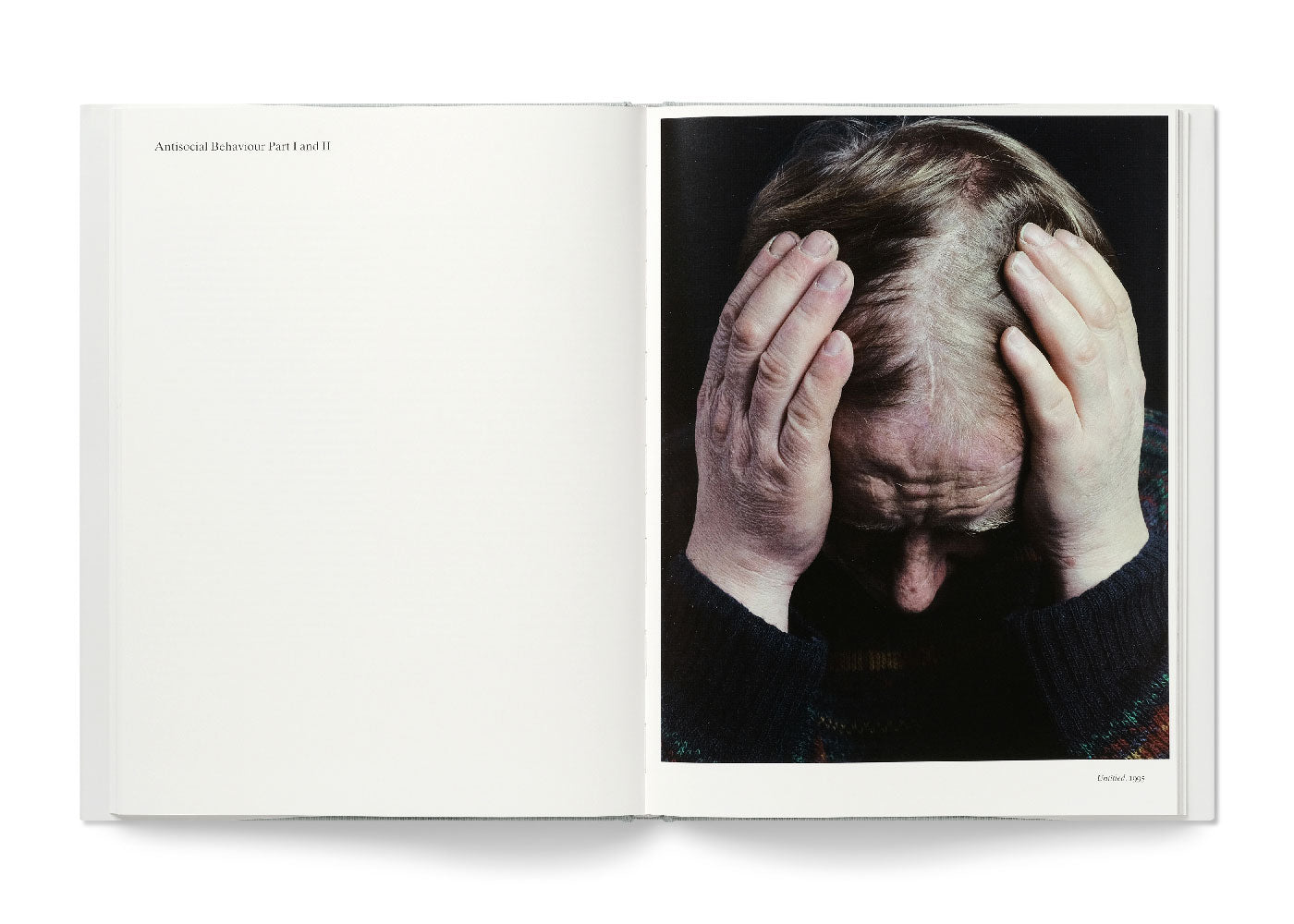

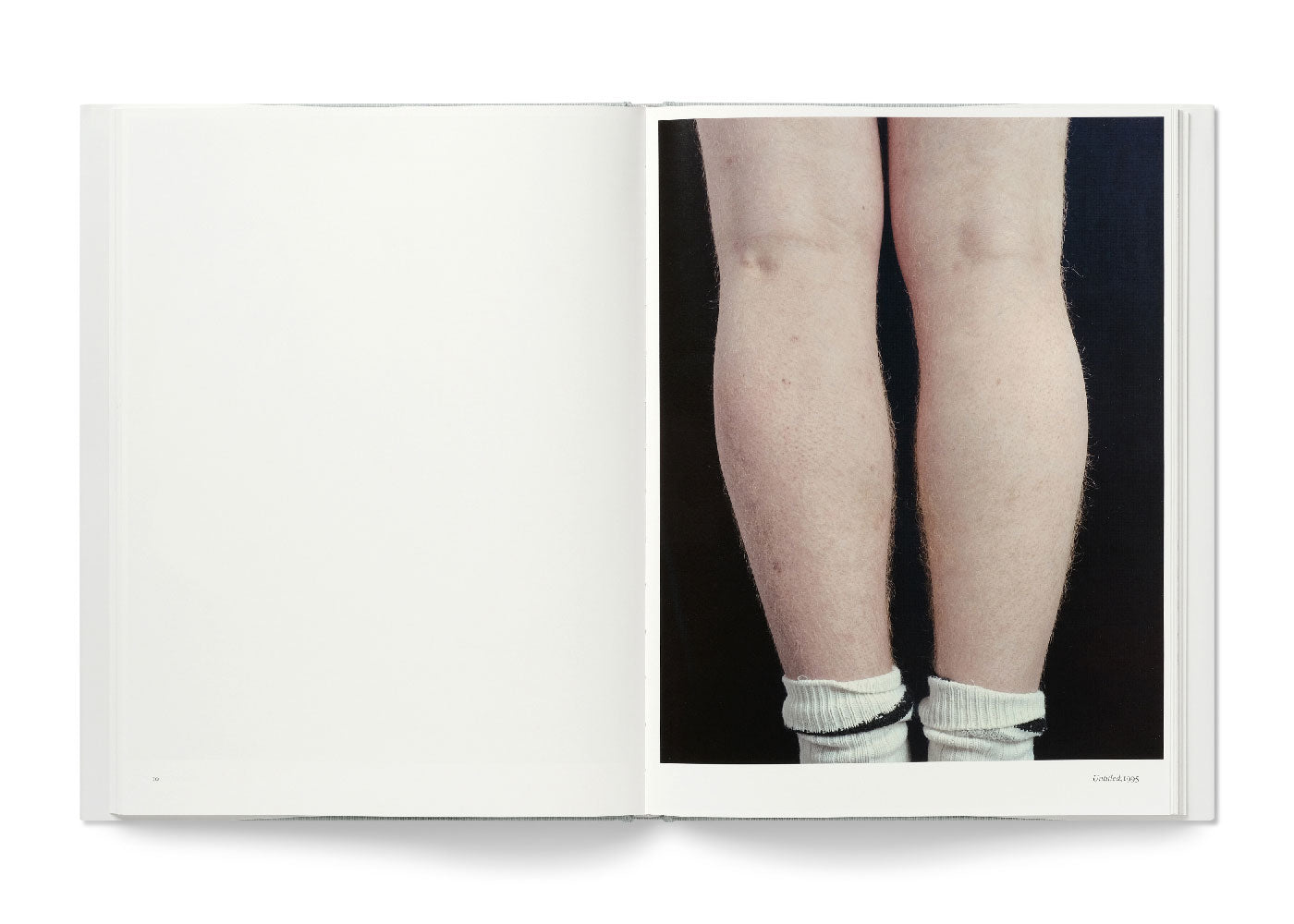

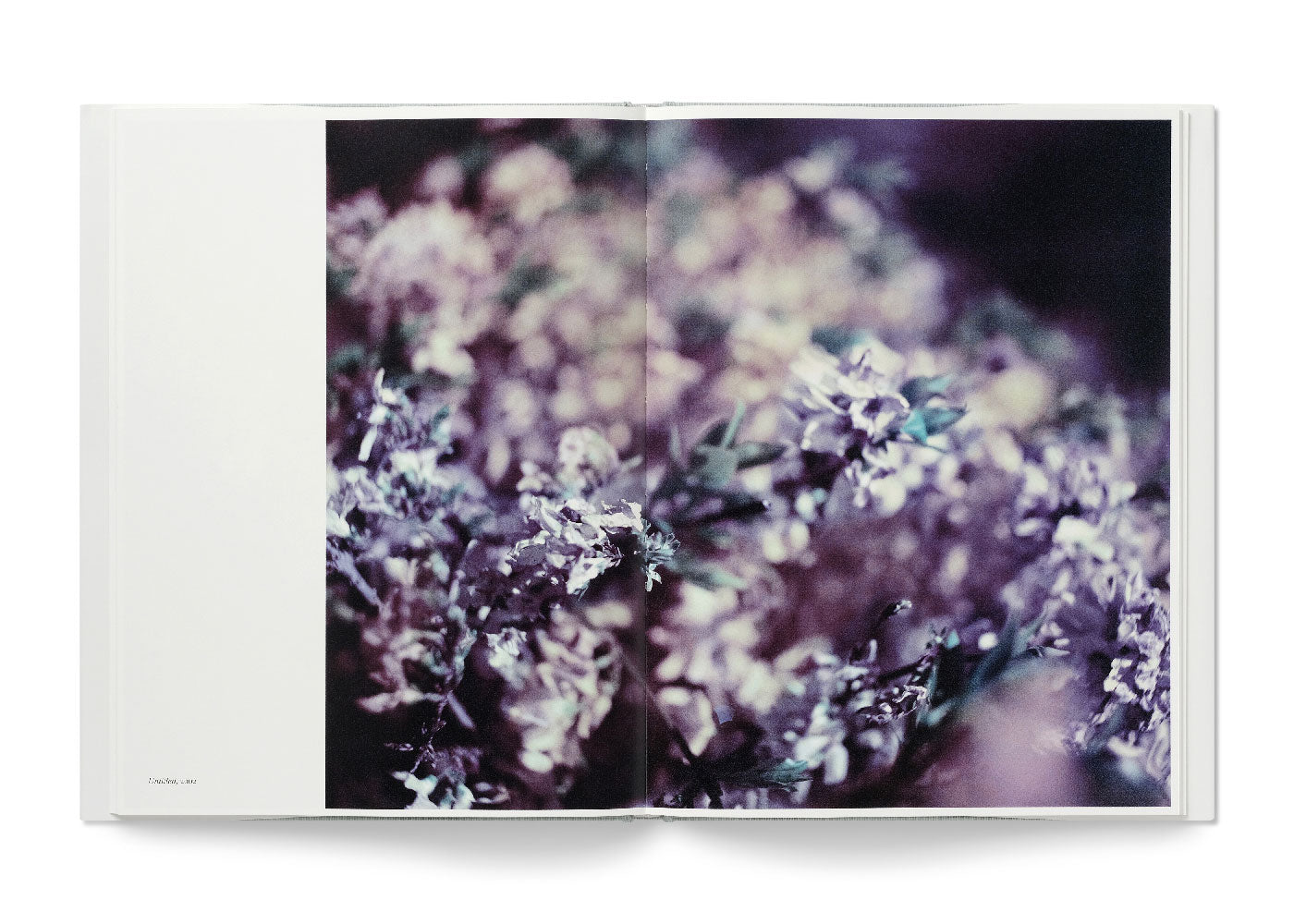

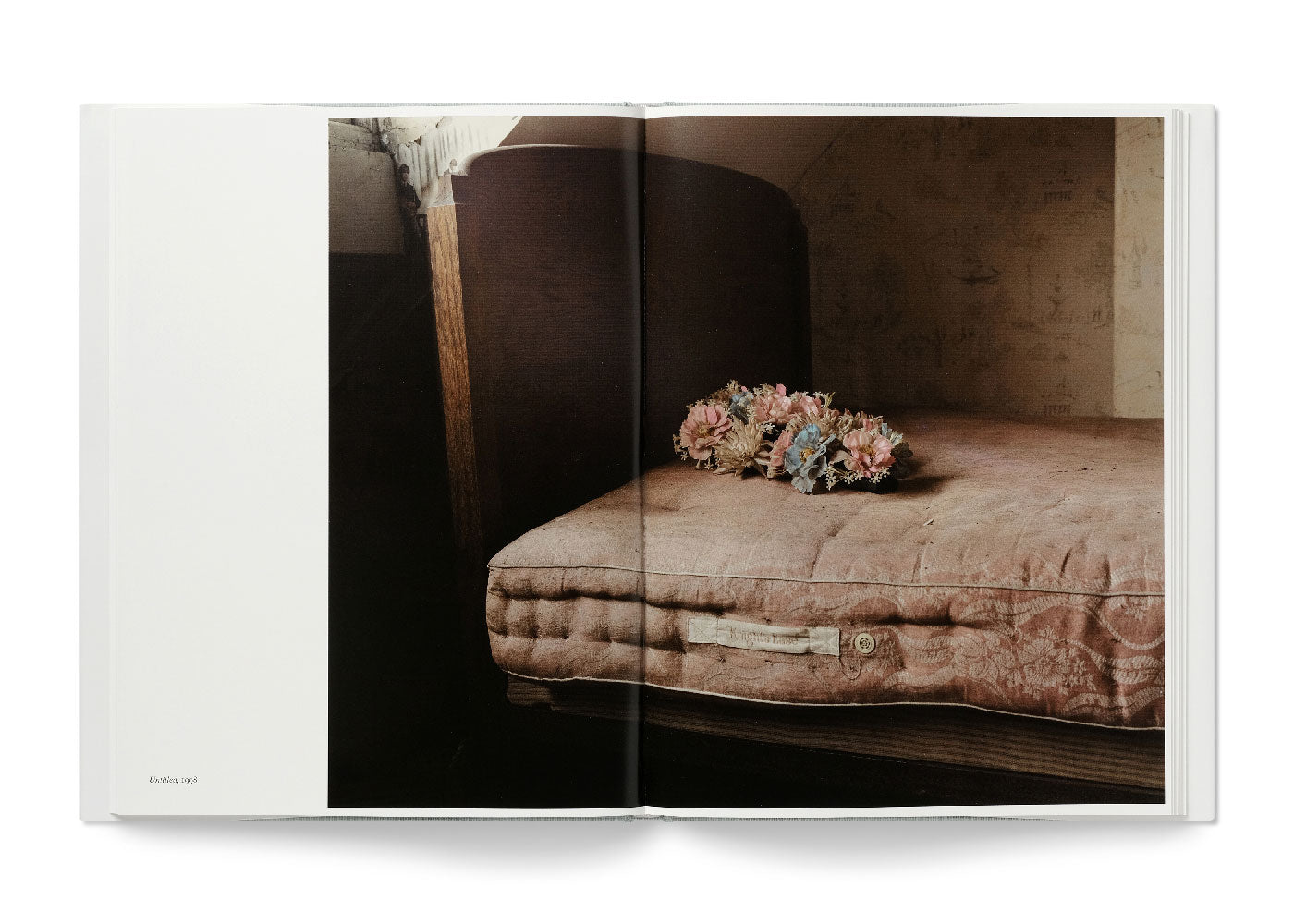

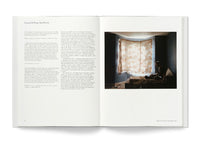

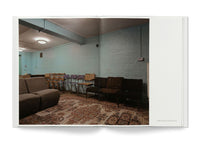

This all might suggest a strongly confessional slant to McConnell’s photography. And that would be partly true, but there is no direct self-scrutiny here. Rather, what stands in place of the confessional in McConnell’s work is its particular sense of intimacy. Especially in his portraits, as lookers and outsiders, we are continually brought close to his subjects, sometimes too close for comfort. Feeling a little like unwanted guests, arriving anyway after the event, we are invited into the space of personal connection and are made aware, as Neal Brown has pointed out in his essay later in this book, that the making of the picture has involved some process of sharing. The photographer’s presence is strongly felt, not as an intruder but as a confidant, a fellow traveller – someone conversant with the unspoken language. And this constitutes a form of discovery; in that speculative dialogue between photographer and subject something registers and ignites, and something of beauty is released. McConnell’s Night Flowers series, which on first impression may be quite difficult to place in his work, is perhaps some form of metaphor for this – a simple epiphany on a journey home, one that might sustain the spirit or mark a change in thinking.

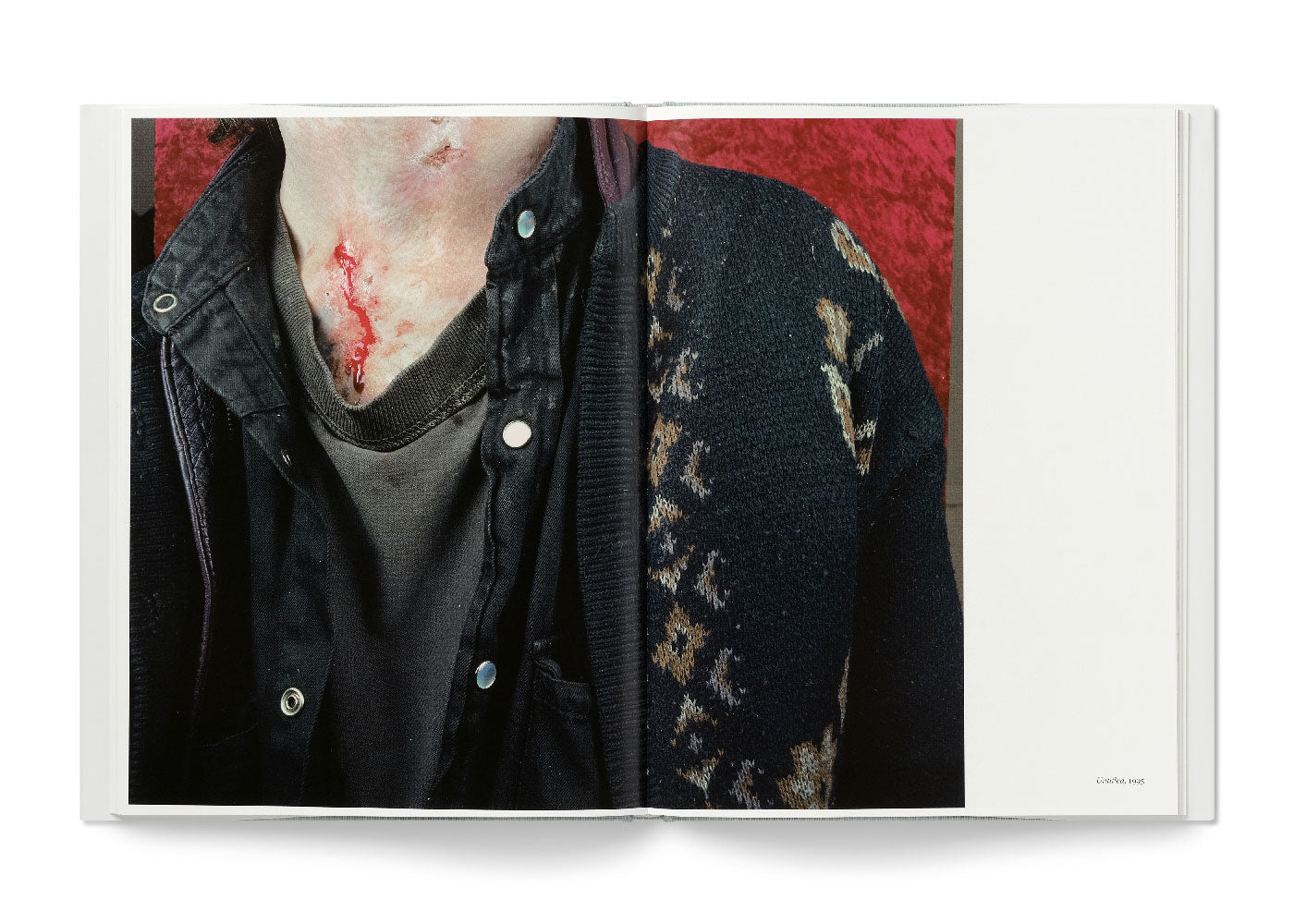

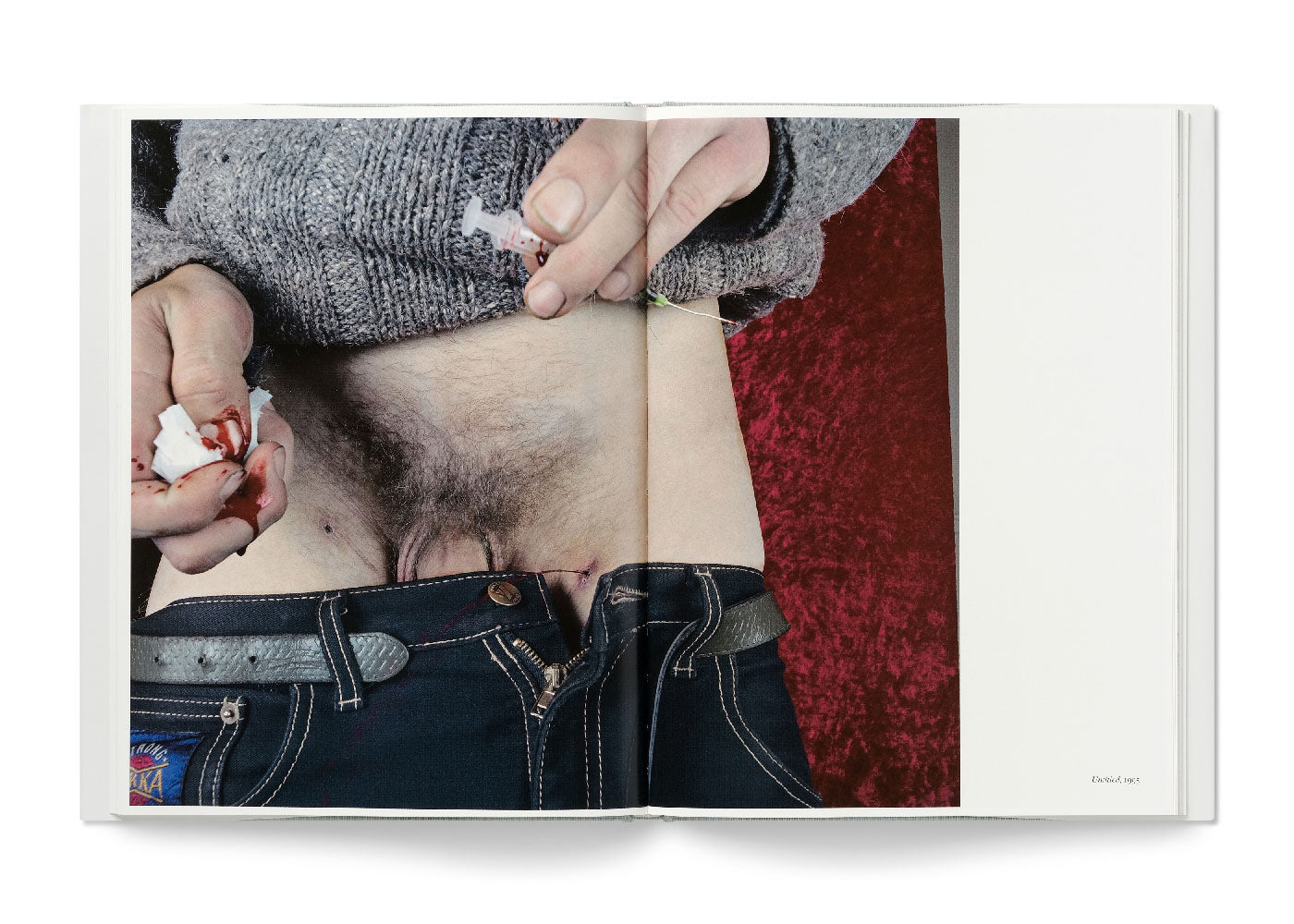

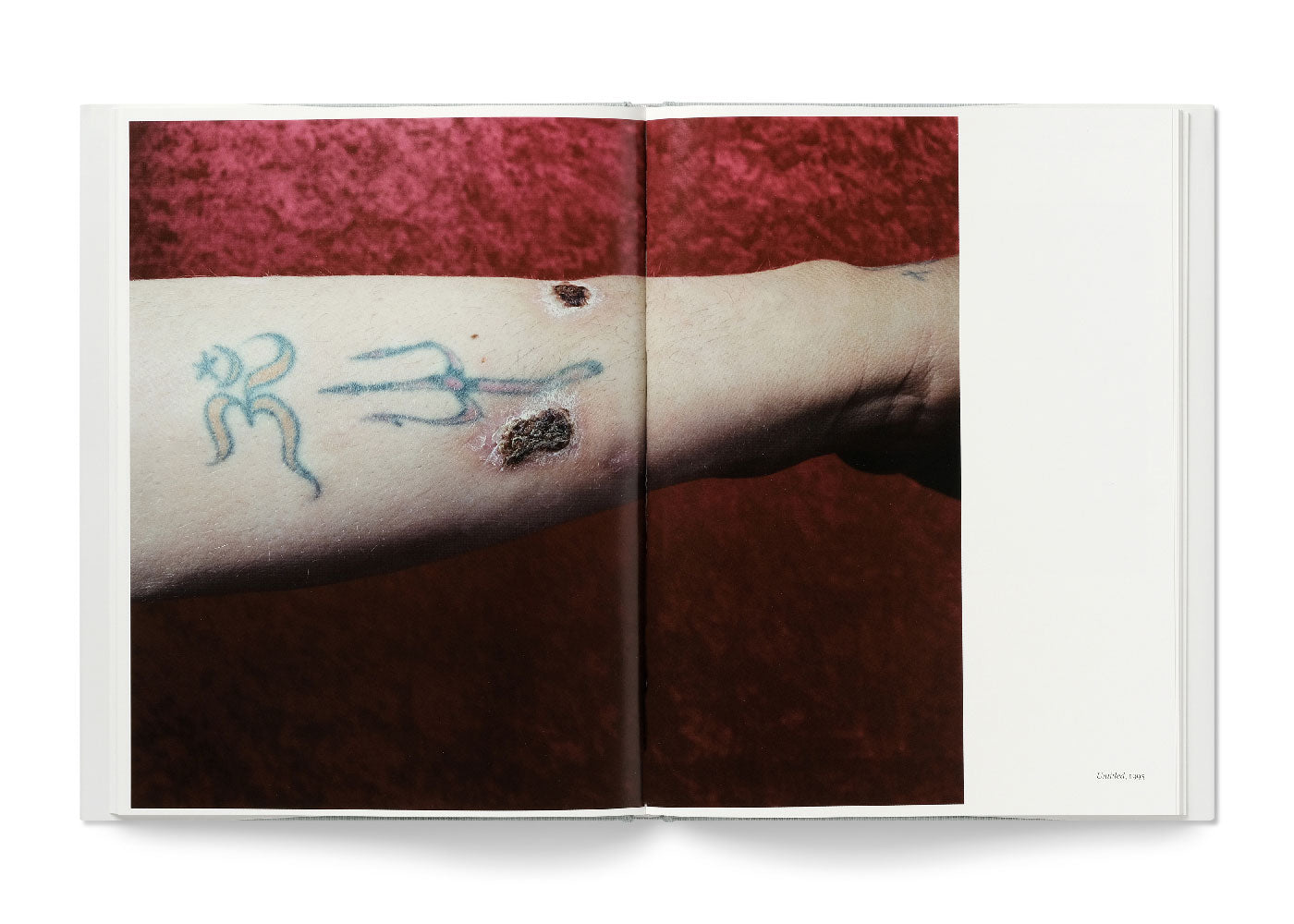

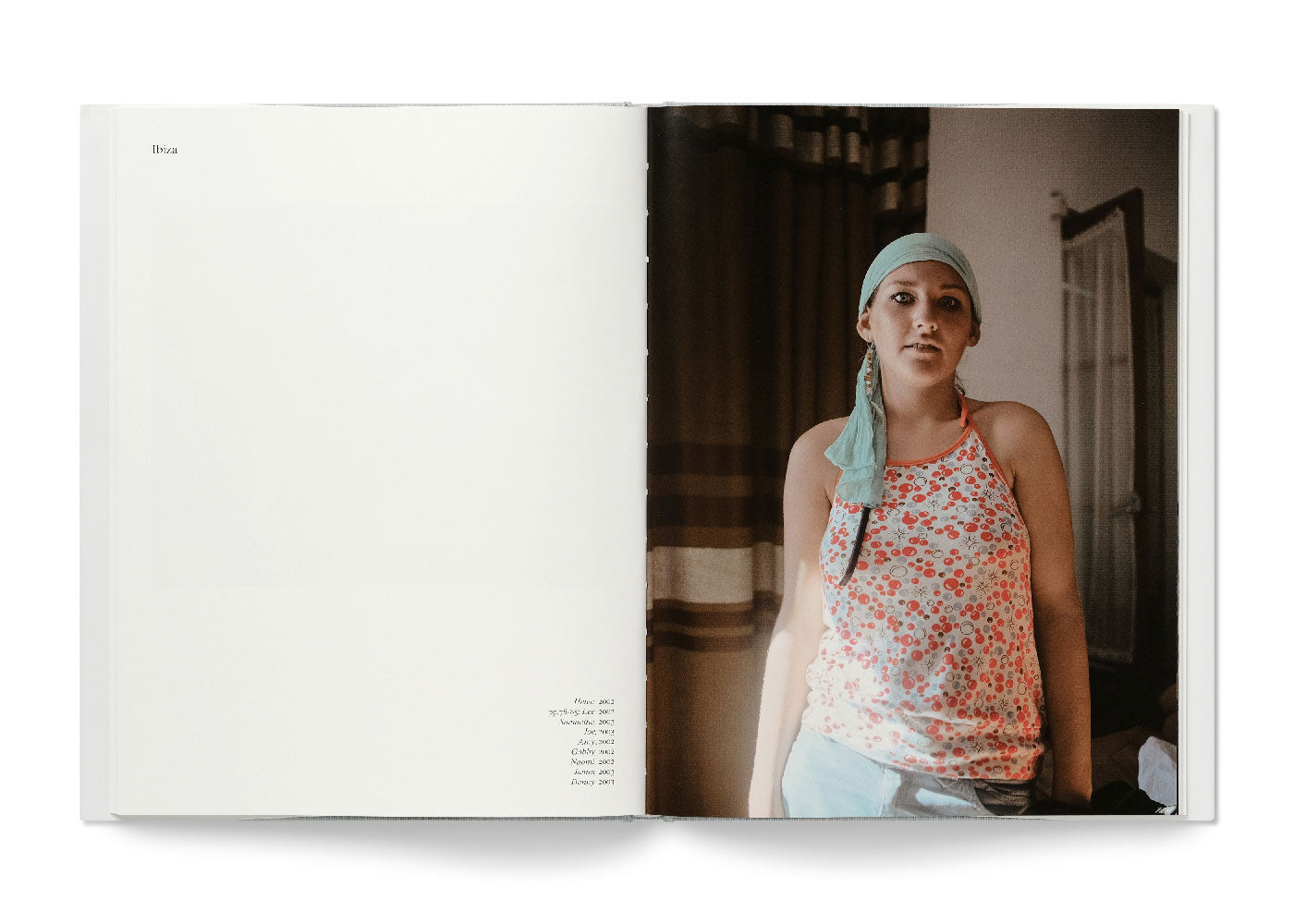

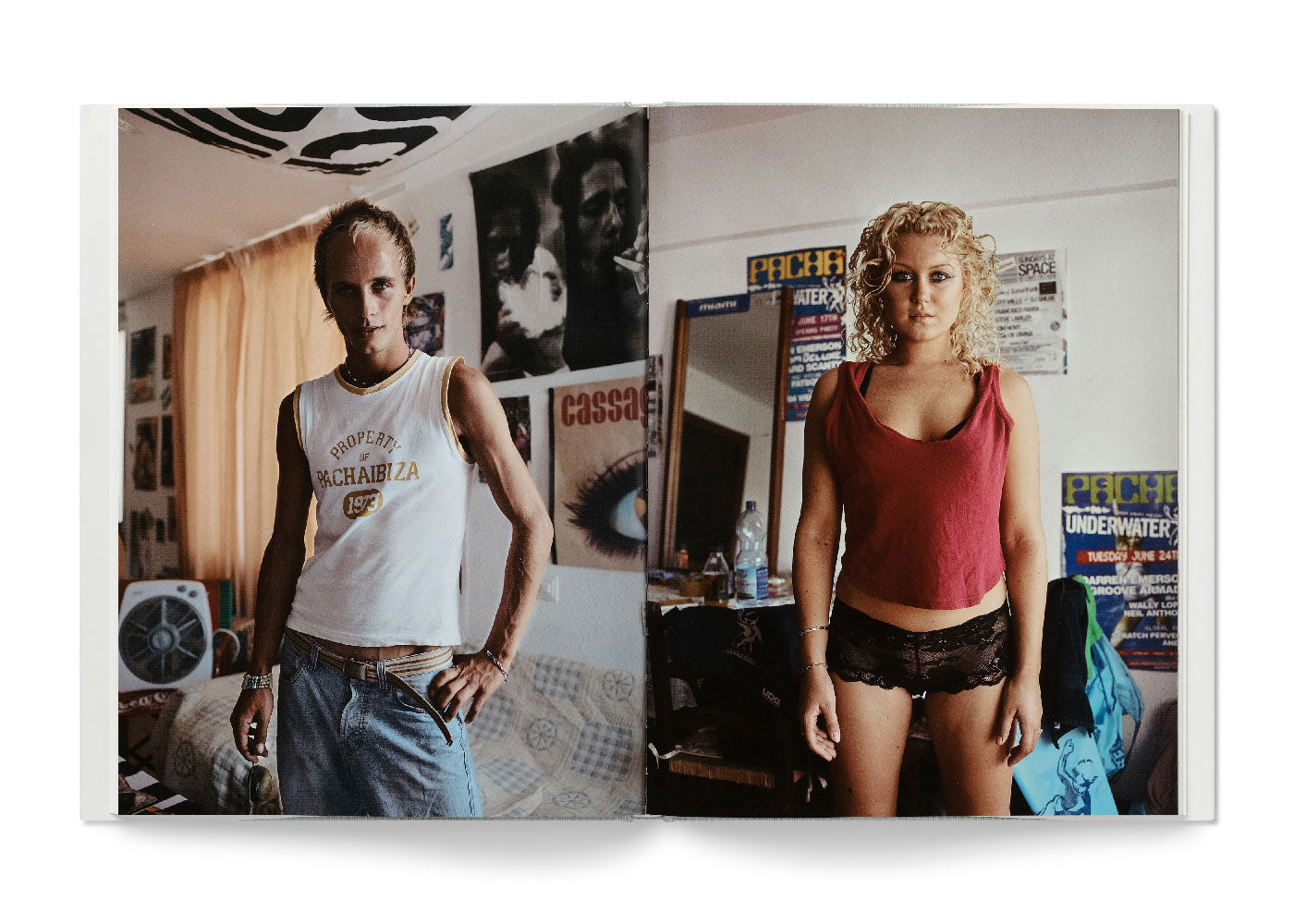

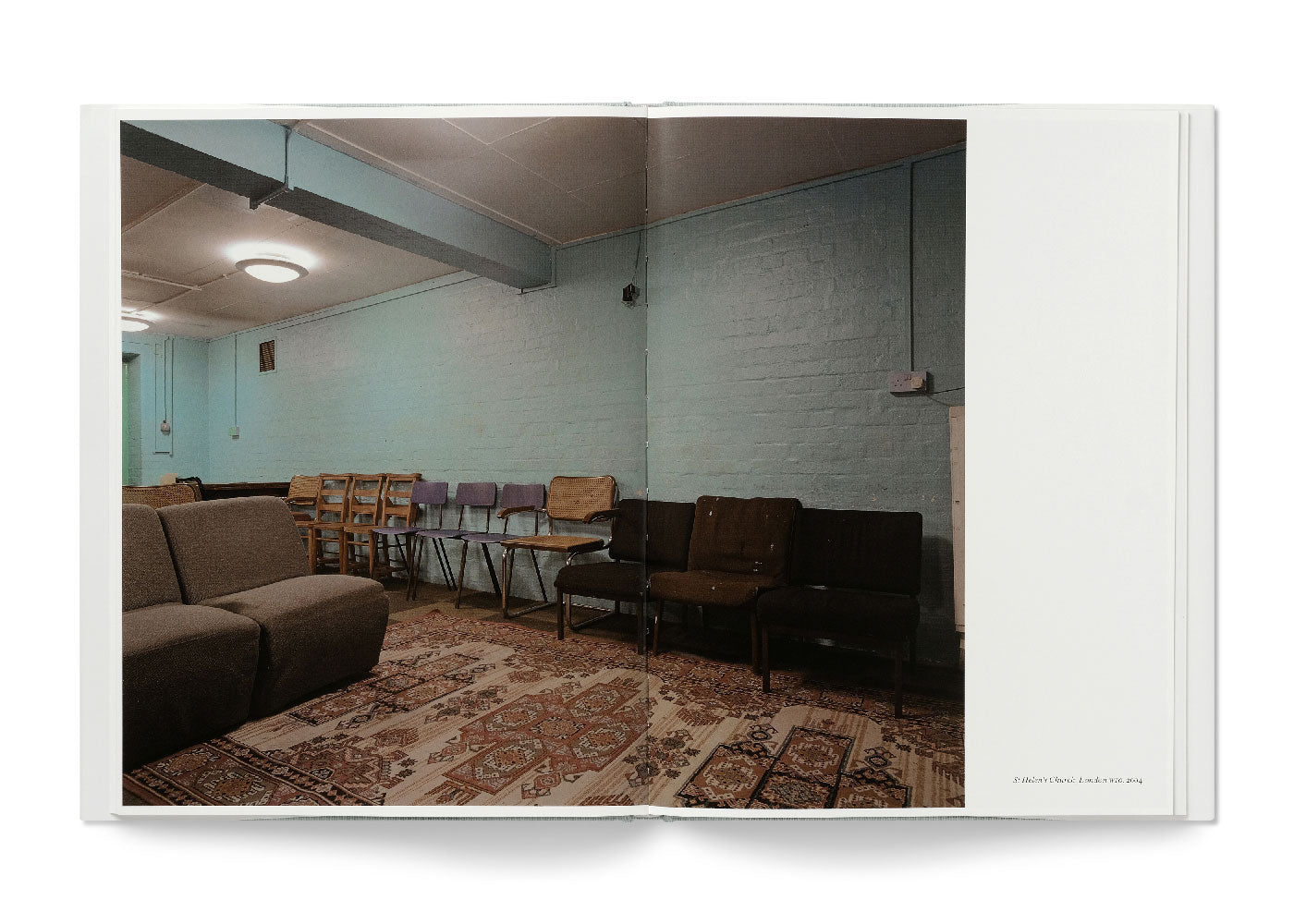

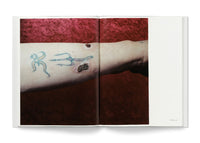

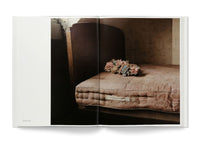

Underlying these encounters in McConnell’s intimate, shared spaces is the varying status of the body, the physical self, as a measure of, or question about identity. In photograph after photograph the body is either casually asserted; it is proffered, abused, exposed, reclaimed and recovered. At times the body’s limits are tested and then a sense of equilibrium is achieved. But journeying through McConnell’s work, from the straight-backed young woman in the Albert Bar, readying herself for the camera, to the alternately energised and exhausted young veterans of the Ibiza lifestyle, we are made aware of the strenuous effort to stabilise the body, to control it and reconcile it with some other uncertain image of the self.

This idea of the destabilised body, of the self coming in and out of focus, appearing and disappearing – both as an image and as a physical presence – is reflected and painfully chronicled in Simon Pooley’s text later in this book. But Pooley’s story also provides another fitting context for McConnell’s experience and work in its suggestion of a positive end to this cycle, a re-emerging from the point of disappearance, a final closure. Neal Brown, in his essay, also refers to McConnell’s work, and his journey, in terms of a ‘reconstruction’ – the peace-building ‘that must take place after the war’.

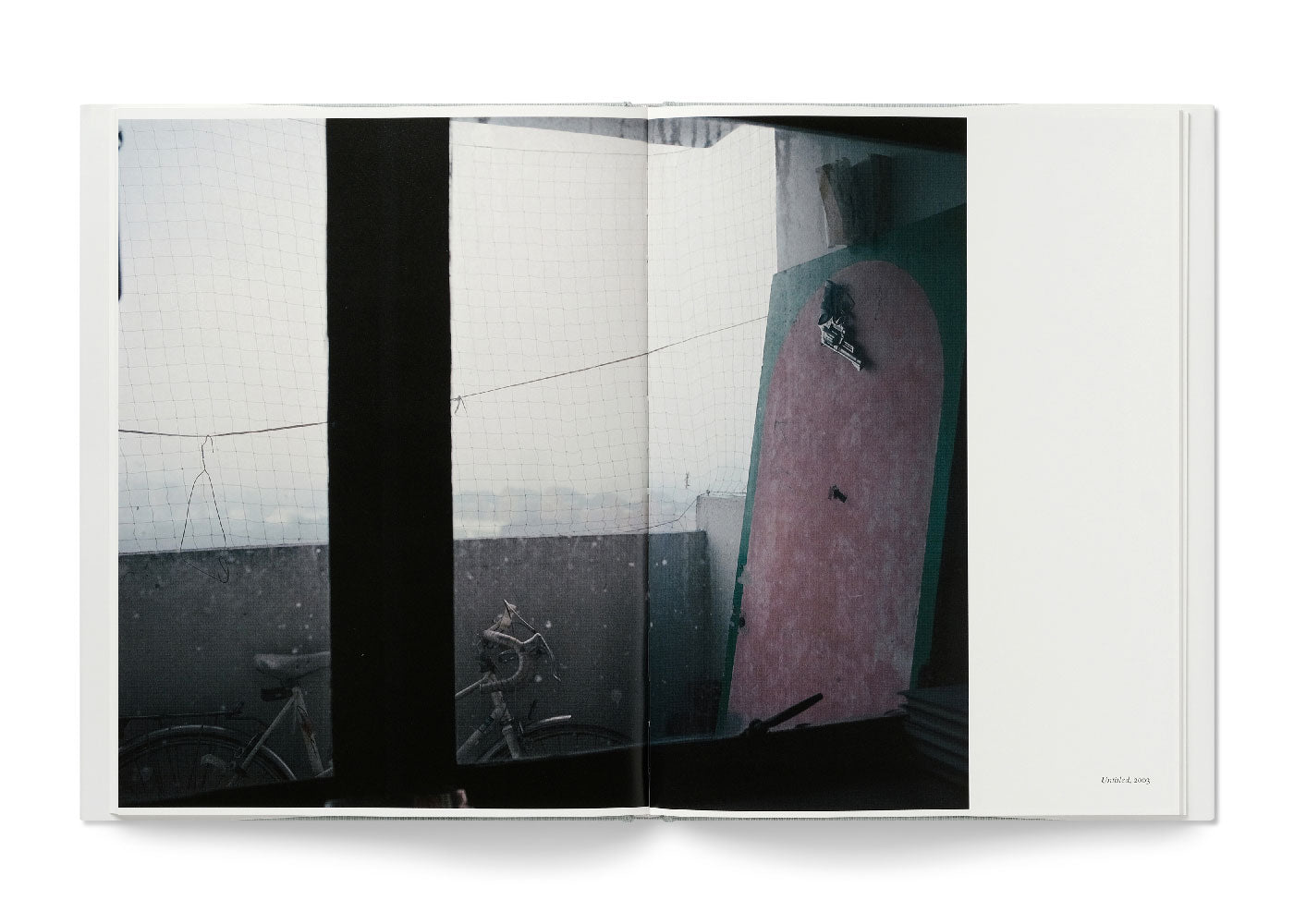

The last word in relation to this sense of reconstruction in McConnell’s work must fall on the subject of light: that property, after all, which conditions any act of appearance or disappearance. Often made over long exposures, McConnell’s photographs emphasise stillness, composure and the slow time of reflective duration. And the light that spreads a muted chiaroscuro across these pictures is a redemptive light, softening space, bringing shape and substance to McConnell’s bodies and giving grace to their claims on identity.

David Chandler

Read More...